Is Christianity Unscientific?

Neo-atheist Sam Harris alleges that the faith of Christian geneticist Francis Collins is unscientific:

James Watson, the co-discoverer of the structure of DNA, a Nobel laureate, and the original head of the Human Genome Project, recently [asserted] in an interview that people of African descent appear to be innately less intelligent than white Europeans. A few sentences, spoken off the cuff, resulted in academic defenestration… Watson’s opinions on race are disturbing, but his underlying point was not, in principle, unscientific… there is, at least, a possible scientific basis for his views. While Watson’s statement was obnoxious, one cannot say that his views are utterly irrational or that, by merely giving voice to them, he has repudiated the scientific worldview and declared himself immune to its further discoveries. Such a distinction would have to be reserved for Watson’s successor at the Human Genome Project, Dr. Francis Collins.[1]

How should one understand and respond to the accusation that Christianity is ‘unscientific’?

Defining ‘Science’

The term ‘science’ comes from the Latin scientia, which means ‘knowledge’; a concept that subsumes, and so fails to specify, what contemporary usage means by the word. Indeed, as philosophers Steven B. Cowan and James S. Spiegel observe: "Defining science is problematic, to say the least…".[2] Bruce L. Gordon reports that "There is no consensus among philosophers of science as to what constitutes a proper scientific explanation or what criteria a theory must possess in order to be truly scientific. Despite extensive attempts, criteria that indisputably demarcate science from non-science or pseudo-science have never been offered."[3] Consequently, "Philosophers of science are much less optimistic than they were a few decades ago about the possibility of finding any really coherent demarcation criteria."[4] Samir Okasha suggests that:

science is a heterogeneous activity, encompassing a wide range of different disciplines and theories. It may be that they share some fixed set of features that define what it is to be a science, but it may not… Wittgenstein argued that there is no fixed set of features that define what it is to be a 'game'. Rather, there is a loose cluster of features most of which are possessed by most games. But any particular game may lack any of the features in the cluster and still be a game. The same may be true of science.[5]

The question ‘Is x science?’ may be like the question of whether or not a pile of sand is a dune. We can’t say exactly how many grains of sand makes a dune, but that doesn’t stop us distinguishing between a grain of sand on the one hand and a dune on the other. As J.P. Moreland says: "One can recognize clear examples of science without a definition … and clear cases of non-science… But these are at opposite ends of a continuum with fuzzy boundaries and several borderline cases."[6] In a rough and ready sense, then, I propose to define ‘science’ as:

- A first-order discipline involving systematic inquiry into the physical world, the primary aim of which is to know (understand, explain and/or predict) as much as we can about physical reality.

Whatever else it is, science is a first order discipline (being a first order discipline is a necessary but non-sufficient criterion of being scientific). Questions about the nature of science aren’t scientific questions. Hence science cannot be defined in terms of a commitment to naturalism and it can’t rule out philosophical knowledge about non-physical realities. Scientists may be committed to naturalism, but science is not.

Indeed, science is neither epistemologically nor ontologically omnicompetent; that is, it doesn’t encompass every way of knowing or everything about which we can know. To claim otherwise is self-contradictory. The statement "Science is omnicompetent" isn’t a first order statement of science, but a second order (philosophical) statement about science; one that denies the possibility of second order statements about science!

Defining ‘Christianity’

Christianity is a spirituality; that is:

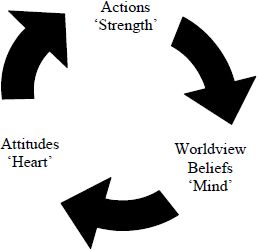

- A ‘form of life’ or way of relating to reality – to ourselves, to each other, to the world around us and (most importantly) to ultimate reality – via worldview beliefs, attitudes and actions.

Jesus’ filled out this generic structure in a specific way when he taught that true spirituality is receiving God’s offer of forgiveness and relationship made in Christ, loving God: "with all your heart [i.e. your attitudes] ... and with all your mind [including your worldview], and with all your strength [i.e. your actions]" and therefore "to love your neighbor as yourself" (Mark 12:30-32, cf. Deuteronomy 6:5):

Jesus’ Kingdom Spirituality = Love God (and therefore Self & Neighbour) with all your:

When the apostle Peter preaches the gospel in Acts 2:37 his audience naturally respond in these three categories:

"When the people heard this [i.e. when they believed the truth-claims about Jesus and his resurrection], they were cut to the heart [their attitude was one of positive response] and said to Peter and the other apostles, 'Brothers, what shall we do?' [they acted in response]."

The same categories underlie Peter’s command that Christians should "Always be prepared to give [action] an answer to everyone who asks you to give [action] the reason [belief] for the hope [attitude] that you have. But do this [action] with gentleness and respect [attitudes]…" (1 Peter 3:15).

Being Unscientific & Being Anti-Scientific

A response to the accusation that Christianity is ‘unscientific’ needs to disambiguate the concept of being ‘unscientific’ from the concept of being ‘anti-scientific’.

With reference to the modern sense of ‘science’, for something to be ‘unscientific’ is merely for it to be something besides a first-order discipline the primary goal of which is to know as much as we can about physical reality. In the sense that ‘Christianity’ isn’t ‘science’, its obvious that Christianity is ‘unscientific’. But then, so are many other things that one may hold in high esteem. For example, philosophy, maths, art and jam making are all ‘unscientific’! Saying that Christianity is ‘unscientific’ doesn’t appear to be a particularly damning indictment. Clearly, the critic who condemns Christianity by calling it ‘unscientific’ is assuming that there’s something about Christianity that is actually anti-scientific. To be ‘anti-scientific’ something must be in active opposition to some essential element of science.

Merely disagreeing with a scientific theory doesn’t make one anti-scientific. Theories can be scientific without being true, and scientists disagree with each other’s theories all the time. Adopting an anti-scientific position may lead someone to reject a particular scientific theory; but the mere fact that someone rejects a particular theory is no proof that they have adopted an anti-scientific position. Rather, being ‘anti-scientific’ means being committed to a position (a belief, attitude and/or action) in tension with something that unifies participants in the scientific project even when they have scientific disagreements.

What’s objectionable about rejecting a scientific theory for anti-scientific reasons isn’t the rejection of a scientific theory (since one can do that without being anti-scientific). Rather, it’s the fact that one thereby flouts an epistemic virtue that’s bound up in the wise practice of rationality per se. The elucidation and justification of epistemic virtues essential to science is a second order, philosophical matter. Hence, ‘scientific rationality’ cannot be segregated from philosophical rationality. As Robert C. Koons affirms: "science cannot be demarcated from the rest of knowledge".[7] In the final analysis, the charge of being ‘unscientific’ boils down to the charge that one is irrational (note how Harris slides from calling Collin’s faith "in principle, unscientific" to calling it "utterly irrational"). The charge of irrationality assumes that one is flouting or rejecting one or more epistemic virtues; this may be seen as exemplified in one’s rejection of a scientific theory, but it’s one’s rationality that’s on trial.

One’s only options for rebutting a charge of irrationality are as follows:

a) Show that one isn’t flouting or rejecting the relevant purported epistemic virtue.

b) Show that the relevant purported epistemic virtue should be limited in such a way that it isn’t flouted by one’s position.

c) Show that the relevant purported epistemic virtue should be rejected.

For example, the atheist may accuse Christians of being unscientific because "Theism flouts Occam’s razor, which states that we should always chose the simplest explanation – which is clearly naturalism". Simplicity is a virtue. However, the virtue of simplicity is limited by the greater virtue of explanatory adequacy; and while naturalism is a simple worldview, theists may rationally hold that theism is the simplest adequate explanation of reality favoured by a correct formulation of Occam’s razor.

Given the difficulty in stipulating individually necessary and jointly sufficient criteria that define ‘science’, obvious difficulties attend the general accusation that Christianity is ‘anti-scientific’. As Cowan and Spiegel observe: "Defining science is problematic, to say the least… One obvious lesson here is that it is naïve to speak dogmatically about the essence of science or about its superiority or inferiority to other fields of inquiry."[8] However, apologists shouldn’t rely upon this ambiguity since we can agree upon some paradigmatic examples of what it would mean to be ‘anti-scientific’. Despising science, seeking to repress science and flouting sound epistemological virtues are all anti-scientific positions.

Assigning the Burden of Proof

Since being unscientific doesn’t entail being anti-scientific, one can grant the unscientific status of Christianity whilst assigning critics the burden of justifying their assertion that Christianity is anti-scientific. Critics must demonstrate that the Christian necessarily flouts a genuine epistemic obligation qua Christian. It’s important to press critics to be specific here, because the general allegation of being ‘unscientific’ functions as a smokescreen for a variety of allegations. In responding to these allegations, one should consider two questions:

1) Does being a Christian require one to reject this supposedly essential epistemic virtue (notwithstanding the actual beliefs, attitudes and actions of Christian individuals and institutions)?

and,

2) Is the accusation grounded in a sound, properly formulated and properly ranked epistemic virtue essential to the scientific project (and not merely in a disagreement about particular scientific theories)?

Question 1 relates to option a) given above, while question 2 relates to options b) and c). The burden of proof rests with the critic to establish that both criteria are fully satisfied if their objection it is to carry any weight.

Noting the rejection of a particular scientific theory by Christians isn’t a sound objection to Christianity unless this rejection is entailed by some anti-scientific position that one is obliged to embrace qua Christian. Furthermore, noting that some Christians embrace anti-scientific positions doesn’t justify ignoring the question of whether or not one can be a Christian without embracing that position. If position X is anti-scientific but being a Christian is compatible with rejecting position X, then one has an argument against being a Christian who accepts position X, not an argument against being a Christian.

Questions 1 and 2 help us to respond appropriately to objections wrapped in the ‘Christianity is unscientific’ smokescreen. For example, the critic may accuse Christianity of repudiating ‘the scientific worldview’ in rejecting metaphysical naturalism. If so, one should point out that while being a Christian entails rejecting naturalism, a commitment to naturalism isn’t an essential element of science. The objection fails because it fails to satisfy criterion 2.

Alternatively, many accuse Christianity of being anti-scientific because having ‘faith’ means having "belief in the absence of supportive evidence and even in the light of contrary evidence".[9] One need only point out that whilst science repudiates ‘blind faith’ in the teeth of (sufficient) contrary evidence (criterion 2 is satisfied by this objection), so does Christianity (this objection fails to pass criterion 1). The critic has misunderstood the meaning of ‘faith’ within the orthodox Christian tradition. No doubt some Christians share this misunderstanding; but as Tom Price observes: "when the New Testament talks about faith positively it only uses words derived from the Greek root [pistis] which means 'to be persuaded'."[10] Price hits the nail on the head when he comments: "Faith loves logic… because real, authentic faith cares about real things like integrity, and honesty. And it would be pretty odd for a faith to extol these virtues, but require the opposite of them for its initial impulse or conception."[11]

Overlapping Interests

"Science and religion are not mutually exclusive categories." – Steve Fuller[12]

The fact that Christianity is unscientific doesn’t mean that Christianity has nothing to do with science, as if they lived in hermetically sealed compartments (the same thing could be said of philosophy, maths, art and jam making). After all, Thomas Aquinas called theology the "queen of the sciences" who was assisted by her "handmaiden philosophy", and he considered science (under the label ‘natural philosophy’) to be part and parcel of that handmaiden. As Moreland writes: "Christianity claims to be a knowledge tradition and places knowledge at the centre of proclamation and discipleship."[13] This is a key point of commonality between Christianity and science: both are concerned with knowledge.

Christianity and science have numerous overlapping interests. Although science isn’t a spirituality, the three elements of spirituality provide a useful grid within which to explore how science and Christianity share overlapping interests in matters concerning human attitudes (e.g. towards community), axiology (i.e. the transcendental values of truth, goodness and beauty) and epistemology. Science and Christianity share an overlapping interest in human action, including the ethics of scientific research, technological development and care for the environment. They also share an interest in having true beliefs about empirical reality, and thus in adopting wise attitudes towards genuine epistemic virtues.

In each instance that science and Christianity have overlapping interests, one can ask if their perspectives are compatible or incompatible (whether because science, Christianity, or both are wrong about something). If science and Christianity take compatible perspectives on something, one can ask if this compatibility is a matter of coherence (the lack of conflict) or consonance (the presence of support, whether mutual or in either direction).

Debunking the Warfare Myth

"Modern science arose within the bosom of Christian theism… it is a spectacular display of the image of God in us human beings." – Alvin Plantinga[14]

The accusation that Christianity is anti-scientific doesn’t sit well with the fact that "Most of the founders of the scientific revolution were devout Christians who held that in their scientific work they were studying the handiwork of the Creator."[15] According to Thomas Dixon: "Although the idea of warfare between science and religion remains widespread and popular, recent academic writing on the subject has been devoted primarily to undermining the notion of an inevitable conflict..."[16] Indeed, it’s worth noting with Alister McGrath that: "The idea that science and religion are in perpetual conflict is no longer taken seriously by any major historian of science."[17]

Indeed, according to physicist and theologian Ian Barbour, "A good case can be made that the doctrine of creation helped set the stage for scientific activity."[18] Numerous presuppositions of science derive warrant from the theistic doctrine of creation:

• That the natural world is real (not an illusion) and basically good (and hence worth studying)

• That the natural world isn’t divine (i.e. pantheism is false) and so it isn’t impious to experiment upon it

• That the natural world isn’t governed by multiple competing and/or capricious forces (i.e. polytheism is false)

• That the natural world is governed by a rational order

• That the human mind is, to some degree, able to understand the rational order displayed by the natural world

• That human cognitive and sensory faculties are generally reliable

• That the rational order displayed by the natural world cannot be deduced from first principles, thus observation and experiment are required

There is thus a wide-ranging consonance between Christianity and the presuppositions of science:

"Both Greek and biblical thought asserted that the world is orderly and intelligible. But the Greeks held that this order is necessary and that one can therefore deduce its structure from first principles. Only biblical thought held that God created both form and matter, meaning that the world did not have to be as it is and that the details of its order can be discovered only by observation. Moreover, while nature is real and good in the biblical view, it is not itself divine, as many ancient cultures held, and it is therefore permissible to experiment on it… it does appear that the idea of creation gave a religious legitimacy to scientific inquiry."[19]

Agnostic Steve Fuller admits that: "While I cannot honestly say that I believe in a divine personal creator, no plausible alternative has yet been offered to justify the pursuit of science as a search for the ultimate systematic understanding of reality… atheism as a positive doctrine has done precious little for science."[20] He even argues that: "science … makes sense only if there is an overall design to nature that we are especially well-equipped to fathom, even though most of it has little bearing on our day-to-day animal survival. Humanity’s creation in the image of God … provides the clearest historical rationale for the rather specialised expenditure of effort associated with science."[21]

Conclusion

"As sources of authority in the wider society, science and religion have been often polarized – but in ways that do not correspond very clearly to substantive intellectual differences" – Steve Fuller[22]

Christianity is ‘unscientific’ in the sense that it is a spirituality rather than a science; but Christianity isn’t ‘unscientific’ in the sense of being anti-scientific. Hence, faced with the question ‘Is Christianity unscientific?’ one may reply in several ways:

- Yes – in that Christianity isn’t science

- No – in that Christianity isn’t anti-science or irrational

- No – in that science isn’t epistemologically or ontologically omnicompetent

- No – in that Christianity is a knowledge tradition

- No – in that Christians helped give birth to science

- No – in that theism provides metaphysical warrant for the scientific project

Recommended Resources

William Lane Craig, ‘Has Science Made Faith in God Impossible?’, www.reasonablefaith.org/RF_audio_video/Other_clips/A97TAMU01.mp3

Steven B. Cowan & James S. Spiegel, The Love of Wisdom: A Christian Introduction to Philosophy (B&H Academic, 2009)

Garrett J. DeWeese & J.P. Moreland, Philosophy Made Slightly Less Difficult (IVP, 2005)

James Hannam, God’s Philosophers: How the Medieval World Laid the Foundations of Modern Science (Icon, 2009)

Robert C. Koons, ‘The Incompatibility of Naturalism and Scientific Realism’, www.leaderu.com/offices/koons/docs/natreal.html

Robert C. Koons, ‘Science and Belief in God: Concord not Conflict’ in Paul Copan & Paul K. Moser (eds.), The Rationality of Theism (Routledge, 2003), cf. www.robkoons.net/media/69b0dd04a9d2fc6dffff80b3ffffd524.pdf & www.veritas.org/Media.aspx#/v/535

John Lennox, God’s Undertaker: Has Science Buried God? second edition (Lion, 2009) & ‘Has Science Buried God?’, www.cis.org.uk/upload/cis20080428.mov

J.P. Moreland, ‘Is Science a Threat or a Help to Faith? A Look at the Concept of Theistic Science’, www.afterall.net/index.php/papers/18

J.P. Moreland, Christianity and the Nature of Science: A Philosophical Investigation (Baker, 1989)

J.P. Moreland & William Lane Craig, Philosophical Foundations For A Christian Worldview (IVP, 2003)

Paul Nelson, ‘Intelligent Design’, Nucleus (January 2005), www.cmf.org.uk/publications/content.asp?context=article&id=1303

Alvin Plantinga, ‘Science and Religion: Where the Real Conflict Lies’ (2009), www.veritas.org/Media.aspx#/v/837

Alvin Plantinga, ‘Science and Religion: Why Does the Debate Continue?’ (2008), www.veritas.org/Media.aspx#/v/705

Alvin Plantinga, ‘Evolution vs. Atheism’ (2008), www.veritas.org/Media.aspx#/v/802

Alvin Plantinga, ‘An Evolutionary Argument Against Naturalism’ (1995), www.veritas.org/Media.aspx#/v/124 & (1996), www.veritas.org/Media.aspx#/v/86

Del Ratzsch, Science & Its Limits: The Natural Sciences in Christian Perspective (IVP, 2000)

Keith Ward, The Big Questions In Science And Religion (Templeton Foundation Press, 2008)

Peter S. Williams, ‘The Emperor’s New Clothes – Pointing the Finger at Dawkins’ Atheism’, Think (Spring, 2010), http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayFulltext?type=1&pdftype=1&fid=7191812&jid=THI&volumeId=9&issueId=24&aid=7191804

Peter S. Williams, A Sceptic’s Guide to Atheism: God is Not Dead (Paternoster, 2009)

References

[1] Sam Harris, www.project-reason.org/archive/item/the_strange_case_of_francis_collins2/

[2] Steven B. Cowan & James S. Spiegel, The Love of Wisdom: A Christian Introduction to Philosophy (B&H Academic, 2009), p.104.

[3] Bruce L. Gordon, ‘Is Intelligent Design Science?’ in William A. Dembski & James M. Kushiner (eds), Signs of Intelligence: Understanding Intelligent Design (Brazos, 2001), p.201.

[4] Thomas Dixon, Science and Religion: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford, 2008), p.99.

[5] Samir Okasha, Philosophy of Science: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford, 2002), pp.16-17.

[6] J.P. Moreland, Christianity and the Nature of Science: A Philosophical Investigation (Baker, 1989), p.57.

[7] Robert C. Koons, ‘Science and Belief in God: Concord not Conflict’ in Paul Copan & Paul K. Moser (eds.), The Rationality of Theism (Routledge, 2003), p.77.

[8] Steven B. Cowan & James S. Spiegel, The Love of Wisdom: A Christian Introduction to Philosophy (B&H Academic, 2009), pp.104-105.

[9] Victor J. Stenger, The New Atheism (Prometheus Books, 2009), p.45.

[10] Tom Price, ‘Faith is just about “trusting God” isn’t it?’, www.bethinking.org/bible-jesus/beginner/faith-is-about-just-trusting-god-isnt-it.htm.

[11] Tom Price, ‘Loving Logical Faith’, http://abetterhope.blogspot.com/2010/01/loving-logical-faith.html

[12] Steve Fuller, Science vs Religion? Intelligent Design And The Problem Of Evolution (Polity, 2007), p.11.

[13] J.P. Moreland, Kingdom Triangle (Zondervan, 2007), p.76.

[14] Alvin Plantinga, ‘Evolution and Design’, James K. Beilby (ed.), For Faith and Clarity (Baker, 2006), p.212.

[15] Ian Barbour, When Science Meets Religion: Enemies, Strangers or Partners? (SPCK, 2000), p. xi.

[16] Thomas Dixon, Science and Religion: A Very Short Introduction, pp.2-3.

[17] Alister McGrath, The Twilight of Atheism (Rider & Co, 2005), p.87.

[18] Barbour, op cit, p.23.

[19] Ibid, p.23.

[20] Steve Fuller, Dissent Over Descent (Icon, 2008), p.9.

[21] Ibid, p.70.

[22] Fuller, Science vs Religion?, op. cit., p.1.

© 2010 Peter S. Williams

This paper appeared in Norwegian in the Scandinavian apologetics journal Theofilos (www.theofilos.nu/?lang=no) and appears here by the kind permission of the author and Theofilos.