Artistic Responses to the Cross Throughout History

No art depicting the crucifixion exists from the first few centuries after Jesus’ death and resurrection. For an event so well documented, and so repeated, both visually and verbally, this period of artistic silence seems strange.

Furthermore, it is astonishing that Christianity spread across the Roman world unassisted by visual stimuli. The Roman era was a period of political propaganda, where emperors demonstrated their rule through abundant images of themselves on coins, seals, and sculptures. It seems remarkable, then, that without any visual aid, people were choosing to make Jesus their Lord and Saviour.

There are many possible reasons for the lack of images of the crucifixion throughout the early church. One is that Judaism discouraged visual imagery.[1] Another is that there were no records of Jesus’ appearance. He left no physical remains, so relics were not appropriate. Even the tomb he occupied only very briefly was not his own. In a culture so saturated in images of the crucifixion, where the cross has even become a symbol of Christianity, it is strange to imagine a time when these images were used primarily to mock and to shame.

A piece of graffiti from around the year 200 may be the first depiction we have of Christ on the cross. It shows a donkey-headed figure, backside in full view, fixed to a cross. A Roman guard looks up to him, raising an arm in veneration. The accompanying inscription reads ‘Alexamenos worships [his] God’.[2] This is demonstrative of how the early Christians were mocked for praising a God on the cross. It also shows how the cross would have been a symbol of humiliation, equivalent to the gallows or electric chair, rather than, as Christians have come to view it, a picture of victory over death. It is apt that the first depiction of Christ on the cross is in mockery, as it can be viewed as a more authentic re-enactment of the original moment.

It is apt that the first depiction of Christ on the cross is in mockery

This article looks at visual retellings of Christ’s crucifixion throughout art history, told in loosely chronological order according to the details included in Mark’s Gospel. This is to avoid the erroneous assumption that different periods of art history exclusively drew different meanings from the crucifixion. Traditions do emerge, but individual responses are manifold at every point in history; a rich healthy ruler and an impoverished hospital patient will perhaps look to the cross differently. Artists’ responses are testament to the depth and complexity of the original event, of which the message is profoundly simple and eternal: Christ died for our sins.

Victory through death

The paradoxical nature of Jesus’ crucifixion has always been problematic for artists aiming to depict the significance of the event. One such question posed to artists is how to depict life in death. Christ was beaten, humiliated, and led to a torturously slow death. How to depict this bleak moment of the crucifixion whilst keeping in sight that through dying Christ achieves victory over death?

The paradoxical nature of Jesus’ crucifixion has always been problematic for artists

A sarcophagus from the middle of the fourth century in the Museo Pio Christiano has on it the scenes of Christ’s passion carved in relief.[3] There is a detectable reluctance to depict the suffering of Christ, possibly for fear of ridicule, as aforementioned. Jesus is represented here as a calm, strong, young beardless Roman holding a scroll, a convention of depictions of philosophers. The cross is empty, but present, alluding to the event but not directly describing Jesus’ execution. The cross in the central scene doubles as a reference to the empty tomb, before which the guards sit. Above, two doves, symbolising peace, peck at an enormous wreath. Wreaths in the Roman era were representative of victory. In all but one of the scenes depicted here, a wreath is present.[4] The presence of the wreaths and doves on the sarcophagus, itself a clear demonstration of death, would have been a visual reminder that death has been defeated, and that the deceased believer will one day rise from their tomb to be with the resurrected Jesus.

Dignity with humility

Another problem facing artists, was how to depict Christ as King, and yet humbled to death on a cross. A sign reading ‘King of the Jews’ hung above his thorn-crowned head, but how to demonstrate the truth which this joke at the time unconsciously pointed to?[5] The Lothair cross from around the year 1000 draws upon the extreme humility demonstrated through the cross. It was made for Holy Roman Emperor Otto III but donated to Aachen Cathedral as soon as it was made, where it is still used in processions today.[6]

On the bejewelled front is a cameo showing the bust of the Emperor Augustus, indicating how the Ottonian dynasty believed themselves heirs to the Roman civilisation.[7] On the back is a simple outline of Jesus hanging on the cross, engraved in the undecorated gold. This would have faced the sovereign during processions. A saying of Matilda, the mother of Otto I, was ‘Dignity with Humility’. [8] This cross was similarly a reminder of Christ’s kingship and triumph and yet extreme humility as something to be aspired to by the Ottonian rulers.

One artist who emphasised perhaps more than anyone before him the suffering and degrading death of Christ on the cross is Mathias Grünewald. On the front of his Isenheim Altarpiece, Grünewald painted an image of Christ contorted in pain, thorns sticking out of his deathly grey skin, covered in wounds from being beaten. The folding altarpiece was painted between 1512–16 for the church of the monastic hospital of the Canons Regular of St Anthony, where sufferers of ergotism (or St Anthony’s fire) were treated.[9] Patients visiting the chapel to receive prayer for healing would see an image of a saviour who suffered with them and knew their pain. Ultimately, this would also work as a reminder that pain belonged to a world in a state of sinfulness, and here was an image of a body which had absorbed all the sins of the world.[10]

Salvador Dalí, in his Christ of Saint John of the Cross (1951), actively sought to create the opposite feeling to Grünewald’s altarpiece. He wrote

I want to paint a Christ that is a painting with more beauty and joy than have ever been painted before. I want to paint a Christ that is the absolute opposite of Grünewald’s materialistic savagely anti-mystical one.[11]

Dalí wrote in 1952 that he wanted to achieve the opposite feeling than most modern painters ‘who have interpreted [Christ] in the expressionistic and contortionistic sense, thus obtaining emotion through ugliness. My principal preoccupation was that my Christ would be beautiful as the God that he is.’[12] To create his image of beauty, Dalí drew upon a Spanish tradition which emerged in the seventeenth century of depicting Christ on the cross not so much in pain, but totally alone, surrounded by darkness.[13] Dalí however gives us a view of Jesus as though looking down from heaven. The shift in perspective when our eyes venture around the painted landscape below, though disconcerting, gives a sense of a Christ as always present. Depicted between the fragile world and God, Christ intercedes for us with arms outstretched, embracing the whole world from the cross.[14]

Horror and humiliation

A more contemporary depiction of Christ on the cross is American artist and photographer, Andres Serrano’s Immersion (Piss Christ). This photograph from 1987 shows a small plastic crucifix submerged in a glass tank of the artist's urine. Unsurprisingly many took offence to such treatment of an image of Jesus, however, it is possible that this work brings together the beauty and tradition of Christ embracing the world, alone and forsaken, and the feeling of disgust and shame that is appropriate for any image of torture and death.

Serrano thought we had grown too familiar with traditional depictions of the cross, saying in one interview, ‘the fact that we are not horrified when viewing such an image does Jesus a disservice’.[15] Reflecting on Serrano’s Piss Christ, art historian Adrienne Chaplin calls to mind a sermon in which she heard the preacher say, ‘My muck is smeared all over Jesus on the cross’.[16] Serrano’s work excellently describes the degrading death of Jesus both through the cheapness of the plastic figurine and through the revolting substance in which it is submerged.

Rachel Howard’s show Repetition is Truth – Via Dolorosa at Newport Street Gallery takes inspiration from the stations of the cross, ‘Via Dolorosa’ (‘The way of sorrow’) being the path taken by Jesus on his way to be crucified. The semi-abstract paintings, made between 2005 and 2008 by applying vast swathes of household gloss paint to the canvas, are a commentary of the universality of human rights abuses.[17] They are studies of Ali Shallal al-Qaisi, the Iraqi detainee who was photographed being tortured by American soldiers in Abu Ghraib prison in 2003.[18]

When these images of Ali Shallal al-Qaisi hooded and standing on a box in a cruciform position were released in 2004, Howard became interested in the box. She explained,

The box is almost like a plinth – I was thinking about the cross, the crucifixion, and how it related to this box as a twenty-first century place of horror, humiliation and human rights atrocities, and I couldn’t help but connect the two.[19]

Howard’s work is a cry for the silent, hidden suffering of many without voices, finding expression through history’s ultimate event of injustice, the perfect Son of God, beaten, mocked, and nailed to a cross for a slow, agonising death.

Commotion and comprehension

Whilst many artists throughout history have chosen to show the crucifixion in a pared-down way, emphasising Christ suffering alone, many have chosen to draw on the commotion and chaos of the event. The artist of the large full-page painting of the crucifixion in the Rohan Hours (1420–27) was able to depict Christ as the King of the cosmos, not by donning him with a kingly crown or showing him as strong, as many artists had done, but by emphasising the cosmic events at his death.

In Mark 15:33 we read that ‘At noon, darkness came over the whole land until three in the afternoon.’ The artist, taking inspiration for the composition from the Anjou Bible, replaced its gold leaf sky with a deep blue pattern of angels, picked out with gold outline, each with distraught white faces and wrung hands.[20] The effect is a dark turbulent sky peppered with gold and white stars. The zig-zag of lances, the surging muddle of horses, officials, and disciples below, and the angled views of the crosses of the two thieves emphasises the pivotal role of Christ on the cross central to the composition, square to the picture frame. This contrast serves to demonstrate Jesus as being the centre of the universe. Mark 15:39 reads: ‘When the centurion, who stood there in front of Jesus, saw how he died, he said, “Surely this man was the Son of God!”’ The artist of the Rohan Hours decided to show us how Christ died, so the reader might understand who he was, and the spiritual significance of what he did on the cross.

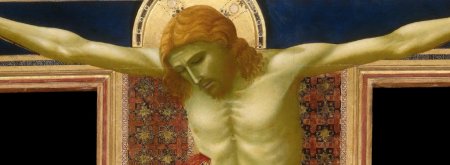

‘Seeing’ underwent an enormous focus in fourteenth century Italy, where both the physicalities of optics were theorised over, but also different types of understanding were discussed in relation to sight. At this time, art was frequently referred to during sermons, interacted with in ceremonies, and used in devotionals as vehicles of meditation. Fra Giordano da Pisa, resident of Santa Maria Novella in Florence, in 1303 identified three levels of vision: that of the bodily eye, the mind’s eye, and the imprinting of God on the soul.[21] The main purpose of the myriad images in churches was so that seeing through the bodily eye might lead to apprehension with the spiritual ‘eye’.

The crucifixion is an event which demands a response from us

Giotto’s huge crucifix (1288–90), over five meters high and four meters wide, hung in Santa Maria Novella, perhaps centrally above the rood beam. It served visually as another cross for the high altar, which would be sometimes hidden from the laity when the church screen doors were closed. While preaching on 13 May 1303, Giordano compared Moses’ bronze serpent to Christ on the cross. To be healed from snake bites in the wilderness, the Israelites were told to gaze on the serpent. To be freed from the snares of the devil, Giordano compelled those present to gaze on and contemplate Christ on the cross. At this point, it is easy to imagine Giordano gesturing to the crucifix hanging in the centre of the church. During a sermon on a similar theme on 11 April 1305, Giordano elaborated

If you gaze at it only with bodily eyes, you will not be healed. Or, even if you look at it with the mind’s eye, this still will not heal you. But do you want to be free and saved? Yes? You must gaze so that you have within you some likeness of him, otherwise your looking is not looking.

The crucifixion is an event which demands a response from us. Here we have seen the traces of people’s responses from throughout history. Some have mocked, while some have seen it as hope of their own resurrection. Some have looked to the beauty of the cross in this light, and the love of the perfect Son of God. Many have seen his sacrifice and humble rule as something to be aspired to. Others have seen his death as the pivotal moment of history, with cosmic confirmation. As the torrent of art on this subject suggests, a response to the cross is demanded of each of us. Rather than respond to a response, perhaps the earliest, first-hand record of the events that took place can give us a better understanding of whether to take it or leave it.

References

[1] Rowena Loverance, The British Museum: Christian Art, (The British Museum Press, 2007), p.24.

[2] David L. Balch and Carolyn Osiek, Early Christian Families in Context: An Interdisciplinary Dialogue, (Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2003), p.103.

[3] Victoria Emily Jones, The Crowning of Christ, (ArtWay, 2015).

[4] The Rt Revd Lord Harries, ‘Christian Themes in Art: The Passion in Art Transcript’, Gresham Lecture, (Museum of London, 12th January 2011), p.2.

[5] Mark 15:17 and 26

[6] Robert G. Calkins, Monuments of Medieval Art, (Dutton, 1979), p.115.

[7] The Rt Revd Lord Harries, ‘Christian Themes in Art: The Passion in Art Transcript’, Gresham Lecture, (Museum of London, 12 January 2011), p.3.

[8] The Rt Revd Lord Harries, ‘Christian Themes in Art: The Passion in Art Transcript’, Gresham Lecture, (Museum of London, 12 January 2011), p.3.

[9] Nigel Spivey, Enduring Creation: Art, Pain and Fortitude, (Thames & Hudson, London, 2001), p.104.

[10] Nigel Spivey, Enduring Creation: Art, Pain and Fortitude, (Thames & Hudson, London, 2001), p.104.

[11] Salvador Dalí, The Unspeakable Confessions of Salvador Dalí, (1976), p.217.

[12] Quoted in the Scottish Art Review, vol IV, no. 1, (1952), p.5.

[13] The Rt Revd Lord Harries, ‘Christian Themes in Art: The Passion in Art Transcript’, Gresham Lecture, (Museum of London, 12 January 2011), p.5.

[14] Susanna Avery-Quash, ‘The Abiding Presence’, in The Image of Christ: The catalogue of the exhibition ‘Seeing Salvation’, (National Gallery, London, 2000), p.195.

[15] Adrienne Chaplin, ‘Portraying Jesus in urine is art not blasphemy – A response to Serrano’s Immersion’ (29 September 2016).

[16] Adrienne Chaplin, ‘Portraying Jesus in urine is art not blasphemy – A response to Serrano’s Immersion’ (29 September 2016).

[17] Newport Street Gallery, Press Release, ‘Rachel Howard solo exhibition to be presented at Newport Street Gallery in February 2018’, 2018, p.1.

[18] Newport Street Gallery, Press Release, ‘Rachel Howard solo exhibition to be presented at Newport Street Gallery in February 2018’, 2018, p.1.

[19] Newport Street Gallery, Press Release, ‘Rachel Howard solo exhibition to be presented at Newport Street Gallery in February 2018’, 2018, p.1.

[20] Marcel Thomas, The Golden Age: Manuscript Painting at the Time of Jean, Duc de Berry, (Chatto & Windus, London, 1979), p.102.

[21] Joanna Cannon, Religious Poverty, Visual Riches, (Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2013), p.52.