Is there really solid evidence for the resurrection of Jesus?

The followers of Jesus said he had risen from the dead. They reported that he appeared to them during a period of forty days, showing himself to them by many ‘convincing proofs’ (Acts 1:3, some versions say ‘infallible proofs’). Paul the apostle said that Jesus appeared to more than 500 of his followers at one time, the majority of whom were still alive and could confirm what Paul had written (1 Corinthians 15:3–8).

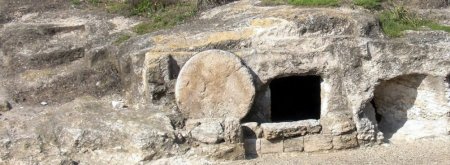

A.M. Ramsey writes: ‘I believe in the Resurrection, partly because a series of facts are unaccountable without it.’[1] The empty tomb was ‘too notorious to be denied.’ Paul Althaus states that the resurrection ‘could not have been maintained in Jerusalem for a single day, for a single hour, if the emptiness of the tomb had not been established as a fact for all concerned.’[2]

Paul L. Maier concludes: ‘If all the evidence is weighed carefully and fairly, it is indeed justifiable, according to the canons of historical research, to conclude that the tomb in which Jesus was buried was actually empty on the morning of the first Easter. And no shred of evidence has yet been discovered in literary sources, epigraphy, or archaeology that would disprove this statement.’[3]

Then how can we explain the empty tomb? Can it possibly be accounted for by a natural cause?

Based on overwhelming historical evidence, Christians believe that Jesus was bodily resurrected in time and space by the supernatural power of God. The difficulties of belief may be great, but the problems inherent in unbelief present even greater difficulties.

The situation at the tomb after the resurrection is significant. The Roman seal was broken, which meant automatic crucifixion upside down for those who did it. The large stone was moved up and away from not just the entrance, but from the entire massive sepulcher, looking as if it had been picked up and carried away.[4] The guard unit had fled. Justin in his Digest 49.16 lists eighteen offenses for which a guard unit could be put to death. These included falling asleep or leaving one’s position unguarded.

The theories advanced to explain the resurrection from natural causes are weak; they actually help to build confidence in the truth of the resurrection.

The Wrong Tomb

A theory propounded by Kirsopp Lake assumes that the women who reported the body missing had mistakenly gone to the wrong tomb. If so, then the disciples who went to confirm the women’s statement must also have gone to the wrong tomb. We can be certain, however, that the Jewish authorities, who had asked for that Roman guard to be stationed at the tomb to prevent the body from being stolen, wouldn’t have been mistaken about the location. Nor would the Roman guards, for they were there.

If a wrong tomb were involved, the Jewish authorities would have lost no time in producing the body from the proper tomb, thus effectively quenching for all time any rumor of a resurrection.

Swoon Theory

Popularized by Venturini several centuries ago and often quoted today, the swoon theory says that Jesus didn’t really die; he merely fainted from exhaustion and loss of blood. Everyone thought him dead, but later he was resuscitated and the disciples thought it to be a resurrection.

The skeptic David Friedrich Strauss – himself no believer in the resurrection – gave the deathblow to any thought that Jesus merely revived from a swoon:

‘It is impossible that a being who had stolen half-dead out of the sepulcher, who crept about weak and ill, wanting medical treatment, who required bandaging, strengthening and indulgence, and who still at last yielded to his sufferings, could have given the disciples the impression that he was a Conqueror over death and the grave, the Prince of Life, an impression which lay at the bottom of their future ministry. Such a resuscitation could only have weakened the impression which He had made upon them in life and in death, at the most could only have given it an elegiac voice, but could by no possibility have changed their sorrow into enthusiasm, have elevated their reverence into worship.’[5]

The Body Stolen

Another theory maintains that the body was stolen by the disciples while the guards slept (Matthew 28:1–15). The depression and cowardice of the disciples provide a hard-hitting argument against their suddenly becoming so brave and daring as to face a detachment of soldiers at the tomb and steal the body. They were in no mood to attempt anything like that.

J.N.D. Anderson has been dean of the faculty of law and director of the Institute of Advanced Legal Studies at the University of London. Commenting on the proposition that the disciples stole Christ’s body, he says: ‘This would run totally contrary to all we know of them: their ethical teaching, the quality of their lives, their steadfastness in suffering and persecution. Nor would it begin to explain their dramatic transformation from dejected and dispirited escapists into witnesses whom no opposition could muzzle.’[6]

The theory that the Jewish or Roman authorities moved Christ’s body is no more reasonable an explanation for the empty tomb than theft by the disciples. If the authorities had the body in their possession or knew where it was, why didn’t they just produce the body when the disciples began preaching the resurrection in Jerusalem? Why didn’t they recover the corpse, put it on a cart, and wheel it through the center of Jerusalem? Such an action would certainly have destroyed Christianity.

Dr John Warwick Montgomery comments: ‘It passes the bounds of credibility that the early Christians could have manufactured such a tale and then preached it among those who might easily have refuted it simply by producing the body of Jesus.’[7]

Notes:

[1] Arthur Michael Ramsey. God, Christ, and the World (London: SCM Press, 1969), pp. 78–80.

[2] Paul Althaus. Die Wahrheit des kirchlichen Osterglaubens (Gutersloh: C. Bertelsmann, 1941), pp. 22, 25ff.

[3] Independent, Press-Telegram, Long Beach, Calif., Saturday, April 21, 1973, p. A-10.

[4] Josh McDowell. Evidence That Demands a Verdict (San Bernardino, Calif.: Campus Crusade for Christ International, 1973), p. 231.

[5] David Frederick Strauss. The Life of Jesus for the People (London: Williams and Norgate, 1879, 2nd ed.), Vol. 1, p. 412.

[6] J.N.D. Anderson. Christianity: The Witness of History (Copyright Tyndale Press, 1970. Used by permission of InterVarsity Press, Downers Grove, Ill.), p. 92.

[7] John Warwick Montgomery. History and Christianity (Downers Grove, Ill., InterVarsity Press, 1972), p. 78.

© 2001-2002 Josh McDowell Ministry

Josh McDowell Ministry, 2001 West Plano Parkway, Suite 2400, Plano, TX 75075, USA

Tel: +1 972 907 1000 www.josh.org