The Delusions of Atheists

In my most extreme fluctuations I have never been an atheist in the sense of denying the existence of a God.[1] (Charles Darwin)

In view of such harmony in the cosmos which I, with my limited human mind, am able to recognise, there are yet people who say there is no God. But what really makes me angry is that they quote me for support of such views.[2] (Albert Einstein)

It enjoys no observational support whatever. What is referred to as M-theory isn't even a theory. Indeed it's hardly science. It's a collection of ideas, hopes, aspirations … I think the book is misleading.[3] (Roger Penrose on Stephen Hawking's book The Grand Design)

Kepler breaks into enthusiasm at being the first to recognise the beauty of God's works. Thus the new way of thinking [science] has nothing to do with any turn away from religion.[4] (Werner Heisenberg)

Science is reticent when it comes to the question of the great unity of which we somehow form a part. The popular name for it in our time is God.[5] (Erwin Schrödinger)

Some atheists claim science supports their views. Or does science point to the existence of God?

The Delusions of Christopher Hitchens

I want to look at Richard Dawkins and Stephen Hawking, but first a quick look at another of the New Atheists – Christopher Hitchens, and his book God is not Great, in which he claimed that "religion poisons everything".[6] Hitchens insists that atheists are better behaved than religious people. He wrote:

If a proper statistical enquiry could ever be made, I am sure the evidence would be that more crimes of greed and violence are committed by the faithful than by atheists.[7]

Hitchens tells us:

It is impossible to claim that religion makes people behave in a more kindly or civilised manner.… The worse the offender the more devout he turns out to be. The chance that a person committing crimes was 'faith-based' was almost 100%.[8]

Richard Dawkins also claims that atheists are better behaved than religious people. He referred to a Montreal police strike which led to rioting, looting and arson; Dawkins claimed more of it would have been carried out by religious people than atheists: "My uninformed opinion is that religious believers loot and destroy more than unbelievers."[9] He admits he has no evidence.

In a TV interview, Hitchens was asked to imagine he was in a strange city at dusk, when he was approached in a dark alley by a gang of men. Would he be more worried, if they were religious or atheists? He categorically replied, "I can say absolutely I would feel immediately threatened, if they were coming from a religious service."[10] Here are some more quotes from the book:

As I write these words, and as you read them, people of faith are in their different ways, planning your and my destruction, and the destruction of all the hard-won human attainments.[11]

Violent, irrational, intolerant, allied to racism, tribalism and bigotry, invested in ignorance, and hostile to free enquiry … Religion looks forward to the destruction of the world.[12]

One of the connections between religious belief and the sinister, spoiled, selfish, childhood of our species, is the repressed desire to see everything smashed up, and ruined, and brought to naught.[13]

When an earthquake hits or a tsunami floods, or twin towers ignite, you can see and hear the secret satisfaction of the faithful.[14]

Hitchens claims: "The attitude of religion to medicine is necessarily hostile."[15] He also urged the Church of England to apologise for combatting science and for the Crusades[16] (even though it didn't exist at the time of the Crusades!). He also maintains believers "still claim to know! Not just to know, but to know everything."[17]

He upbraids Jesus for identifying with the poor, with the comment, "What is this, if not populism?"[18] Of the Beatitudes he wrote: "They express fanciful wish-thinking about the meek and the peacemakers."[19] Hitchens also objects to Jesus's comment on lilies! "Consider the lilies of the field, they toil not neither do they spin. Yet I say unto you, that Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed as one of these" (Matthew 6:28-29). Hitchens complains: "The analogy of humans to lilies suggests that thrift, innovation, family life and so forth are a waste of time."[20] Next Hitchens claims that "charity and relief work are the inheritors of modernism and the Enlightenment."[21] Maybe he hasn't heard of the relief work of monasteries in the Middle Ages, or the work of the Salvation Army or of the Emperor Julian, the nephew of the Emperor Constantine, who tried, and failed, to revert to the old Roman gods. Julian reflected that his failure was down to the fact that the Christians not only loved each other, but worse still – from his point of view – they loved non-Christians and helped them.

Hitchens even objects to Jesus's command to love your neighbour as yourself. Why? Because, he says, "The order to 'love thy neighbour as thyself' is too extreme and too strenuous to be obeyed."[22] He goes on: "Humans are not so constituted as to care for others, as much as for themselves: as any intelligent creator would well understand. The thing simply cannot be done. Urging humans to be superhuman, is the urging of a terrible self-abasement at their repeated and inevitable failure to keep the rules, which leads to masochism, hysteria and sadism."[23] Also Hitchens variously described Mother Theresa of Calcutta as a "sanctimonious dwarf", a "hell's angel" and a Nazi death camp Commandant.

You may feel that the best candidate for "not being great" is Christopher Hitchens himself, rather than God. It is amazing that such nonsense could become a Number 1 bestseller on the New York Times list. Incidentally, Hitchen's own brother, the journalist Peter Hitchens, wrote the book The Rage against God describing his own journey from a fanatical atheism to Christian faith.

The Delusions of Richard Dawkins

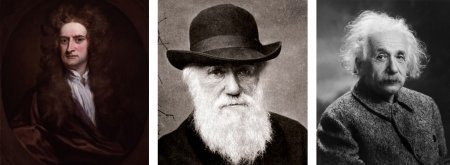

Turning now to Richard Dawkins; he thinks there is a fundamental conflict between science and religion. This would come have as a surprise to some of the greatest names in science: Nicolaus Copernicus (a monk), Johannes Kepler, Galileo Galilei, Isaac Newton, Robert Boyle, Michael Faraday, Joseph Priestley, James Clerk Maxwell, Charles Darwin, Gregor Mendel (the founder of genetics and abbot of a monastery), Lord Kelvin and Albert Einstein. Plus, many of the pioneers of quantum physics: Werner Heisenberg, Max Plank, Erwin Schrödinger, James Jeans, Louis de Broglie, Wolfgang Pauli and Arthur Eddington. And today's scientists – the astrophysicist Paul Davies, Simon Conway Morris (Professor of Evolutionary Paleobiology at Cambridge), Alasdair Coles (Professor of Neuro-immunology at Cambridge), John Polkinghorne (who was Professor of Mathematical Physics at Cambridge), Russell Stannard, Freeman Dyson ... and Francis Collins, who led the team of 2,400 international scientists on the Human Genome Project and was an atheist until the age of 27, when he became a Christian.

Albert Einstein

In the book Real Scientists, Real Faith twenty of today's top scientists, explain why they are believers. As Einstein wrote: "A legitimate conflict between science and religion cannot exist. Science without religion is lame; religion without science is blind."[24] Dawkins explains that some scientists sound religious, but if you delve more deeply into their thinking, they are in fact atheists. He presents Einstein as a prime example, and describes Einstein's religion as pantheism, which he calls "sexed-up atheism".

Dawkins adds that "to deliberately confuse these two understandings of God is an act of intellectual high treason."[25] Strong words indeed! But could it be Dawkins who has committed intellectual high treason? Dawkins wrote this: "Einstein sometimes invoked the name of God, and he is not the only atheistic scientist to do so, inviting misunderstanding by supernaturalists eager to misunderstand and claim the illustrious thinker as their own."[26]

Dawkins cites as his authority in dealing with Einstein's religious views Max Jammer's book Einstein and Religion: "The extracts that follow are taken from Max Jammer's book (which is also my main source of quotations from Einstein himself on religious matters)."[27] However a rather surprising picture emerges when we study what Einstein actually said, as recorded by Jammer in his book Einstein and Religion. Jammer was a personal friend of Einstein and Professor of Physics at Bar-Ilan University in Israel. His book is a comprehensive survey of Einstein's writing, speeches and conversations on God and religion.

I list below ten Einstein quotations from Max Jammer's book from which we can judge whether or not Einstein was an atheist.

- "I am not an atheist, and I don't think I can call myself a pantheist."[28]

- "In view of such harmony in the cosmos which I, with my limited human mind, am able to recognise, there are yet people who say there is no God. But what really makes me angry is that they quote me for support of such views."[29]

- "Every scientist becomes convinced that the laws of nature manifest the existence of a spirit vastly superior to that of men."[30]

- "The divine reveals itself in the physical world."[31]

- "My God created laws… His universe is not ruled by wishful thinking but by immutable laws."[32]

- "I want to know how God created this world.… I want to know his thoughts."[33]

- "What I am really interested in is knowing whether God could have created the world in a different way."[34]

- "This firm belief in a superior mind that reveals itself in the world of experience, represents my conception of God."[35]

- "Behind all the discernible concatenations, there remains something subtle, intangible and inexplicable. Veneration for this force ... is my religion. To that extent I am, in point of fact, religious."[36]

- "My religiosity consists of a humble admiration of the infinitely superior spirit… That superior reasoning power forms my idea of God."[37]

So what does Dawkins conclude? Einstein was an atheist! But Einstein speaks of "a superior spirit", "a superior mind", "a spirit vastly superior to men", "a veneration for this force", etc. This is not atheism.

Now you may be thinking that I have carefully selected quotes that support me and left out ones that don't. But I haven't. Max Jammer explained in his book: "Einstein was neither an atheist nor an agnostic." So my interpretation of what Einstein said, is the same as Max Jammer's. Is it not bizarre, that Dawkins cites in support of his claim that Einstein was an atheist, a book which proves the opposite? Dawkins could also have consulted Lincoln Barnett's book The Universe and Dr. Einstein; Einstein wrote the foreword to it. This quotes Einstein saying:

My religion consists of a humble admiration of the superior spirit, who reveals himself in the slight details we are able to perceive with our frail and feeble minds. That deeply emotional conviction of the presence of a superior reasoning power, which is revealed in this incomprehensible universe, forms my idea of God.[38]

What's more, Einstein complained about atheists, saying: "Then there are the fanatical atheists whose intolerance is of the same kind as the intolerance of the religious fanatics and comes from the same source."[39]

However, Dawkins is right to say that Einstein did not believe in a personal God, who answers prayers and interferes with the universe, nor did he hold an image of God as an old man in the sky. But he did believe in an intelligent mind or spirit, which created the universe with its laws. This is sometimes called deism. Jammer explained: "Einstein renounced atheism, because he never considered his denial of a personal God, as a denial of God. This subtle but decisive distinction has long been ignored." It was ignored by Dawkins.

But, you may say, isn't Einstein's understanding of an impersonal God totally removed from Christian, Jewish and Muslim thinking? Max Jammer thinks not; he refers in his book to the leading Christian theologian Hans Küng, who explained: "Of course, in my youth I had a simple, naïve, anthropomorphic understanding of God. At the beginning of life that is normal. It is less normal for a grown person to preserve their childlike understanding." Eduard Büsching had written a book entitled There is no God and sent it to Einstein. Einstein corrected the title to read There is no Personal God. However in his letter to Büsching Einstein stated: "It is better to believe in a personal God, than to have no transcendent outlook." Moreover Einstein said that his understanding of God could be found in the Bible in the psalms and in the prophets and he commended St Francis of Assisi.[40] So Einstein was – like Newton before him – deeply religious and a firm believer in a transcendent God. If any intellectual high treason has been committed, it has been committed by Dawkins himself.

Incidentally Dawkins has now abandoned the position he set out in The God Delusion. In a debate in 2008 with John Lennox, the Professor of Mathematics at Oxford, held at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, Dawkins conceded there is an arguable case for a God who created the universe, and that the distinguished astrophysicist Paul Davies is a believer in God.[41] [See the YouTube video of the debate, from 3m10s.]

Isaac Newton

If Dawkins' treatment of Einstein is untrue, his treatment of Isaac Newton appears deceitful. Obviously Newton poses a problem for Dawkins. Newton is possibly the greatest scientist of all time, and was a strong believer in God. So how does Dawkins deal with Newton? He tries to neutralise Isaac Newton by claiming he was a fake, motivated by money. This is how he does it – the passage is in Dawkins' book The God Delusion. Dawkins starts with a quote from Bertrand Russell who said: "Intellectually eminent men disbelieve the Christian religion, but hide the fact, because they are afraid of losing their income."[42] The next sentence is: "Newton was religious." The insinuation is that Newton was faking belief in God to get money. This is totally false.

If Newton was faking it, he really overdid it. He wrote to his friend Richard Bentley: "When I wrote my treatise [Principia Mathematica], I had an eye upon such principles as might work for the belief of a deity, and nothing can rejoice me more, than to find it useful for that purpose."[43] He read the Bible every day; attacked and ridiculed atheists and wrote letters encouraging opponents of atheism. Newton wrote:

Gravity explains the motions of the planets, but cannot explain who set the planets in motion. God governs all things, and knows all that is or can be done. This most beautiful system of the sun, planets, and comets, could only proceed from the counsel and dominion of an intelligent Being.[44]

And this: "It is the perfection of God's works, that they are all done with the greatest simplicity. He is the God of order and not of confusion."[45] Galileo said: "The Bible shows the way to go to heaven, not the way the heavens go." Galileo, Newton and Einstein all believed in God, therefore Dawkins' claim that science and religion are in conflict is nonsense.

It was pointed out to Dawkins that many great composers were religious – Tallis, Byrd, Telemann, Bach, Handel, Beethoven, Haydn, Mozart, Mendelsohn, Bruckner and Elgar. He replied that they were all fakes.[46]

What about Charles Darwin?

Richard Dawkins thinks you can't believe in evolution and God. Charles Darwin thought the exact opposite. In his autobiography Darwin wrote:

Another source of conviction in the existence of God, connected with the reason and not with the feelings, impresses me as having much more weight. This follows from the extreme difficulty or rather impossibility of conceiving this immense and wonderful universe, including man with his capacity of looking far backwards and far into futurity, as the result of blind chance or necessity. When thus reflecting I feel compelled to look to a First Cause having an intelligent mind in some degree analogous to that of man; and I deserve to be called a Theist.

This conclusion was strong in my mind about the time, as far as I can remember, when I wrote the Origin of Species; and it is since that time that it has very gradually with many fluctuations become weaker. But then arises the doubt—can the mind of man, which has, as I fully believe, been developed from a mind as low as that possessed by the lowest animal, be trusted when it draws such grand conclusions? ...

I cannot pretend to throw the least light on such abstruse problems. The mystery of the beginning of all things is insoluble by us; and I for one must be content to remain an Agnostic.[47]

Darwin concluded such issues are beyond us. We cannot know the answer to the riddle of the universe. But he wrote On The Origin of Species believing in God. So Dawkins' claim that "Darwinism kicked God out of biology"[48] is a complete misunderstanding of Darwin.

The term 'agnostic' was coined at this time by T.H. Huxley, whose nickname was 'Darwin's bulldog'. It is derived from the Greek word agnotos, relating to 'not knowing'. Darwin is telling us is he does not know the answer to the question of the origin of the universe. Sometimes today we sloppily bracket 'atheist' and 'agnostic' together, as if they meant the same thing. The newly minted word in Darwin's time had a more precise meaning, 'not knowing'. That this should not be confused with the word 'atheist', is made clear by Darwin himself in a letter to John Fordyce of 1879; he wrote this:

It seems to me absurd to doubt that a man may be an ardent theist and an evolutionist. You are right about [Charles] Kingsley. Asa Gray, the eminent [American] botanist, is another case in point.... In my most extreme fluctuations I have never been an atheist in the sense of denying the existence of a God.[49]

So Darwin, on his own account was never an atheist, but fluctuated between theism and agnosticism.

Stephen Jay Gould, a leading American evolutionary biologist, argued science deals with the 'how' questions, and religion with the 'why' questions. According to Gould:

Either half of my colleagues are enormously stupid, or else the science of Darwinism is fully compatible with religious belief – and equally compatible with atheism.[50]

Dawkins commented: "Gould could not have meant what he wrote."[51]

By the way Richard Dawkins likened Martin Rees to a Nazi collaborator ("a compliant Quisling" [see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quisling Ed.]) because he accepted the Templeton Prize, given each year to someone who has advanced the mutual understanding of science and religion.

Another delusion of Dawkins is his belief in the goodness of human nature. He wrote: "I dearly want to believe that we do not need policing – whether by God, or each other – in order to stop us behaving in a selfish or criminal manner."[52] This belief in the goodness of human nature is the bedrock of liberalism and humanism. I examine the evidence against it in my book The Liberal Delusion.[53]

The Delusions of Stephen Hawking

We turn now to Stephen Hawking. He proposes M-theory, a variant of string theory, to explain the origins of the universe. The conclusion of his last book, The Grand Design, states:

Because there is a law like gravity, the universe can and will create itself out of nothing. Spontaneous creation is the reason there is something rather than nothing. It is not necessary to invoke God.[54]

He added: "According to M-theory ours is not the only universe. It predicts that a great many universes were created out of nothing."[55] Therefore, he claims, there is no need for God. The Oxford chemist and atheist Peter Atkins says something very similar to Hawking: "Space-time generates its own dust in the process of its own self-assembly" and "Mathematics created the universe."[56] He calls it the 'Cosmic Bootstrap Principle' after the notion that you can pull yourself up with your own bootstraps. So the universe created itself in exactly the same way.

Hawking's theory is self-contradictory. Hawking wrote: "Because there is a law like gravity, the universe can, and will, create itself out of nothing." But his 'nothing' isn't nothing, rather it is something which contains the laws of gravity. According to Hawking the laws are there already, before a material universe exists. But where did they come from? And how does he know? Can the laws of gravity exist in the absence of matter? Other scientists maintain we can know nothing before the Big Bang. Where does Hawking get his information from? Also isn't Hawking confusing physical laws with agency. It is surely a mistake to think that the laws of physics are agents. Physical laws like gravity don't initiate actions and events. They merely describe the physical universe. Physical laws cannot create anything. A theory can't bring anything into existence.

Apparently no empirical evidence is required, because there is not a shred of evidence for any of this, and since the existence of other universes could never be proved, we are not dealing here with science. The distinction between science and science fiction has become blurred. It was Newton who discovered the laws of gravity; but this didn't lead him to atheism, but to greater belief in God.

One of Britain's most distinguished scientists and a former Astronomer Royal is Martin Rees. He is a long-standing friend and colleague of Hawking's at Cambridge. He was asked, in an interview in The Independent, what he thought of Hawking's views on the existence of God. He replied:

I know Stephen Hawking well enough to know that he has read very little philosophy and even less theology, so I don't think we should attach any weight to his views on God.[57]

Roger Penrose, the leading British mathematician, who worked with Hawking on black holes is another critic of Hawking's theory. He said of M-theory:

It enjoys no observational support whatever. What is referred to as M-theory isn't even a theory. Indeed it's hardly science. It's a collection of ideas, hopes, aspirations… I think the book is misleading. It gives the impression that there is this new theory which is going to explain everything. It's nothing of the sort. I think the book suffers rather more strongly than many. It's not uncommon in popular descriptions of science to latch onto some idea, particularly to do with string theory, which has absolutely no support from observation. They're just nice ideas which people have tried to explore. It's an excuse for not having a good theory. And there's not just one M-theory, there are 10 to the power 500 variants.[58]

Paul Davies in his Templeton lecture said:

Some scientists have tried to argue that if only we knew enough about the laws of physics, then we would find the theory of everything. In other words, the nature of the physical world would be entirely the consequence of logical and mathematical necessity. There would be no choice about it. I think this is demonstrably wrong. There is not a shred of evidence that the universe is logically necessary.[59]

Davies maintains that the theory is not testable, not even in any foreseeable future; and for this reason, M-theory gets a lot of flak from within the science community.

John Lennox, who is Professor of Mathematics at Oxford, comments:

Nonsense is nonsense, even when it is spoken by world famous scientists.… Immense prestige and authority do not compensate for faulty logic.[60]

He points out these are statements by scientists, but not statements of science, because there is no evidence whatsoever to support them. Lennox claims Hawking has performed a triple self-contradiction. Professor Frank Close also of Oxford described it as like poetry or art, having "no experimental evidence"[61] to support it.

The prestigious journal, Scientific American, headed their review of Hawking's book 'Cosmic clowning: Hawking's "new" theory is the same old CRAP.' It went on:

The popularity of M theory stems not from the theory's merits, but from a lack of alternatives, and the stubborn refusal of enthusiasts to abandon their faith.… Hawking is telling us, that unproven M-theory is the end of the quest of science. If we believe him, the joke's on us.[62]

The New Scientist reviewer of The Grand Design was unpersuaded, writing:

M-theory ... is far from complete. But that doesn't stop the authors from asserting that it explains the mysteries of existence... This is nothing more than a doomed hunch.[63]

The Economist is also critical of the book – saying Hawking and Mlodinow:

...claim that their surprising ideas have passed every experimental test to which they have been put, but that is misleading in a way that is typical of the authors. The authors' interpretations have not been subjected to any decisive tests, and it is not clear that they ever could be. Their outlandish theories are in advance of any concrete evidence for them.[64]

Dwight Garner in The New York Times wrote: "The real news about The Grand Design is how disappointingly tinny and inelegant it is."[65]

In his book Not Even Wrong, subtitled 'The Failure of String Theory', the physicist Peter Woit argues that string theory may turn out to be totally vacuous and predict nothing. Roger Penrose commented:

Peter Woit's book is an authoritative and well-reasoned account of string theory's extremely fashionable status among today's theoretical physicists. I regard it as an important book.[66]

Penrose also commented:

The hold that string theory has is very remarkable, considering the lack of any observational support... Woit supplies the first thorough and detailed analysis.[67]

Lee Smolin's book The Trouble with Physics, is subtitled 'The Rise of String Theory, the Fall of a Science and What Comes Next'. According to Smolin:

There needs to be an honest evaluation of the wisdom of sticking to a research program [string theory] that has failed after decades to find any grounding in experimental results, or in precise mathematical formulation. String theorists need to face the possibility that they are wrong and others right.[68]

Robert Laughlin of Stanford University and winner of the 1998 Nobel Prize for Physics stated: "String theory is the tragic consequence of an obsolete belief system."[69]

Hawking dogmatically argued, and bet, that the Higgs boson would never be found. Peter Higgs in 1964 proposed the particle existed. There was a heated public debate between Hawking and Higgs. The latter criticised Hawking's work and complained that Hawking's "celebrity status gives him instant credibility that others do not have."[70] The particle was discovered in July 2012 at CERN following construction of the Large Hadron Collider. Hawking conceded that he had lost his bet.

Does science prove the existence of God?

Atheists like to think that science supports their worldview, but could the opposite be the case? The astronomer Fred Hoyle said scientific discoveries had "greatly shaken" his faith in atheism. He reflected on the energy needed to produce large quantities of carbon, and wrote this:

Some supercalculating intellect must have designed the properties of the carbon atom, otherwise the chance of my finding such an atom through the blind forces of nature would be utterly minuscule.… A superintellect has monkeyed with physics, as well as with chemistry and biology... The numbers one calculates from the facts seem to me so overwhelming as to put this conclusion almost beyond question.[71]

There are many examples of the physical laws being fine-tuned for life: if the force of gravity and electromagnetism, as well as the mass of sub-atomic particles, were ever so slightly different, life on earth would be impossible. If the expansion of the universe had been more even, stars and planets would not have formed. If the forces in the atomic nuclei were weaker, the universe would be made of hydrogen; if stronger, then oxygen would be the base element. If the strength of the strong nuclear force was changed by as small a figure as 0.5 percent then life on earth would be impossible.

The philosopher Antony Flew was Britain's leading atheist before Richard Dawkins. But by 2004 two scientific discoveries had changed his mind. First, the Big Bang theory showed the universe began at a particular point in time. This raises the question, what caused the universe to begin? And second, the universe appears to have been fine-tuned for life. Flew wrote:

Not merely are there are regularities in nature, but they are mathematically precise, universal and 'tied together'. How did nature come packaged in this fashion? Scientists from Newton to Einstein to Heisenberg have answered the Mind of God.[72]

Paul Davies explores these ideas in his book The Goldilocks Enigma. He argues that the universe, like the porridge Goldilocks ate, is 'just right' for life. The evidence for design lies in the laws of the universe. According to Davies, science is based on the assumption that the universe is thoroughly rational and logical. Atheists claim the laws of nature exist reasonlessly and the universe is ultimately absurd.

As a scientist, I find this hard to accept. There must be an unchanging rational ground in which the logical, orderly nature of the universe is rooted.[73]

He argues that the physical laws of the universe have been fine tuned to produce life and consciousness:

The emergence of life and consciousness is written into the laws of the universe in a very basic way.[74]

This does not mean designed to produce the planet Earth and human beings. If the Big Bang were re-run, it would not produce Earth and homo sapiens, but according to Davies, there would be life and consciousness. He added:

I belong to a group of scientists, who do not subscribe to a conventional religion, but nevertheless deny that the universe is a purposeless accident…. There must be a deeper level of explanation. Whether one wishes to call that deeper level 'God' is a matter of taste.[75]

He rejects the multiverse theory, according to which there are billions of other universes, because there is no scientific evidence whatsoever for it, calling it "The last refuge of the atheist."[76]

Roger Penrose, the leading British mathematician, stated:

There is a certain sense in which I would say the universe has a purpose. It's not there by chance. Some people take the view that we happen by accident. I think that there is something much deeper, of which we have very little inkling at the moment.[77]

In addition, many of the pioneers of quantum physics rejected atheism: Heisenberg, Schrödinger, Planck, de Broglie, Jeans, Eddington, Pauli as well as Einstein. Ken Wilber's book Quantum Questions explores their religious writings. Wilber argues that all these groundbreaking physicists believed that spirituality and physics were needed for a full understanding of reality. Wilber poses this question to modern atheists and scientists:

To those who bow to physics as a religion, I ask, what does it mean to you, that the founders of modern science, the theorists who pioneered the very concepts you now worship, were every one of them mystics.[78]

Let me give some examples. This is Heisenberg:

I have repeatedly pondered on the relationship of science and religion, for I have never been able to deny the reality to which they point.

And this:

Kepler breaks into enthusiasm at being the first to recognise the beauty of God's works. Thus the new way of thinking [science] has nothing to do with any turn away from religion.[79]

Max Planck: "There can never be any real opposition between science and religion; for the one is the complement of the other. Every serious and reflective person realizes, I think, that the religious element in his nature must be recognised and cultivated if all the powers of the human soul are to act together in perfect harmony. And indeed it is not an accident that the greatest thinkers of all ages were also deeply religious souls."[80]

Schroedinger: "Science is reticent when it comes to the question of the great unity of which we somehow form a part. The popular name for it in our time is God."[81] And "We know when God is experienced this is as real an event as an immediate sense perception or as one's own personality."[82]

Wolfgang Pauli: "I consider a synthesis of the rational understanding and the mystical experience of unity to be the mythos of the present age."[83]

Arthur Eddington: "I think it a fair analogy for our mystical feelings for nature to apply to our mystical experience of God. Some sense a divine presence irradiating the soul as one of the most obvious things of experience."[84]

Does atheism harm society?

Is atheism harming individuals and society? One of the twentieth century's leading humanists and atheists, H.J. Blackham conceded: "humanists can be put on trial for reducing human life to pointlessness."[85] The atheist Bertrand Russell also concluded that life is meaningless. He wrote:

Man is the product of causes which had no prevision of the end they were achieving; his origin, his growth, his hopes and fears, his loves and beliefs are but the outcome of the accidental collocations of atoms; no fire, no heroism, no intensity of thought and feeling can preserve an individual beyond the grave; all the labour of the ages, all the devotion, all the inspiration, all the noon-day brightness of human genius are destined for extinction in the vast death of the solar system.[86]

The astrophysicist Paul Davies maintains atheism is not merely mistaken, but also damaging to society and individuals. He said:

Our secular age has led many people to feel demoralised and disillusioned, alienated from nature, regarding their existence as a pointless charade in an indifferent, even hostile and meaningless universe. Many of our social ills can be traced to the bleak worldview, that 300 years of mechanistic thought have imposed; a worldview in which human beings are presented as irrelevant observers.… We have to find a framework of ideas that provides ordinary folk with some broader context to their lives than just the daily round, a framework that links them to each other, to nature and to the wider universe in a meaningful way. Yet among the general population there is a widespread belief that science and theology are forever at loggerheads. I regard the universe as a coherent, rational, elegant and harmonious expression of a deep and purposeful meaning.[87]

It is interesting that just as scientists became mystics, so within Christianity there has been a growing interest in mystical or contemplative Christianity and the rediscovery of the mystics of the past such as the desert fathers and mothers. This growing contemplative movement is associated with the names of Thomas Merton, John Main, Richard Rohr and Cynthia Bourgeault. Moreover there is a widespread harmony in the understanding of the divine across widely disparate cultures and times, according to Aldous Huxley. His book, The Perennial Philosophy, is an exploration of mysticism across different religions, periods and civilisations. What is remarkable, he claims, is the degree of unanimity among them. His book contains an anthology of mystics from a wide variety of times and places. There are similar mystical utterances from widely differing races, religions, periods and places.

What do philosophers make of all this? In the last century logical positivists used to attack religious belief on the grounds that it could not be verified; whereas scientific statements were true, because they could be verified. What is puzzling now, is to find scientists claiming that their theories are true, not because they can be verified, but because they are beautiful; as if science had become a subset of aesthetics. And Karl Popper's criterion for science was that it must be possible to falsify a theory. Hawking's theory can be neither falsified, nor proved, and so, according to Popper, is not science.

Wittgenstein maintained there are truths besides those of science, writing: "When all possible scientific questions have been answered, the problems of life remain completely untouched.… There are, indeed, things that cannot be put into words. They make themselves manifest. They are what is called mystical."[88] And this: "What do I know about God and the purpose of life? I know that this world exists. That something about it is problematic, which we call its meaning. The meaning does not lie in it, but outside it. The meaning of life, i.e. the meaning of the world, we can call God."[89]

The Conflict Myth

The claim that there is a fundamental disagreement between science and religion is known to historians of science as 'The Conflict Myth'. Einstein recognised no such conflict, indeed he thought the opposite, writing:

After the God of fear, then the God of morality, there is a third stage of religious experience. I call it cosmic religious feeling. It is very difficult to elucidate to anyone who is entirely without it.… The individual feels the futility of human desires and the sublimity and marvelous order, which reveal themselves both in nature and the world of thought. The beginning of this cosmic religious feeling can be found in the Psalms and in the Prophets [of the Old Testament]. Religious geniuses of all ages have been distinguished by this kind of religious feeling, which knows no dogma and no God image conceived in man's image.[90]

John Lennox explains that the conflict myth has become embedded in the popular mind: "A mythical conflict is hyped, and shamelessly used in another battle between naturalism and theism."[91] In the words of Colin Russell, Professor of the History of Science at the Open University:

The common belief that the relations between religion and science over the last four centuries have been marked by a deep and enduring hostility … is historically inaccurate, a caricature so grotesque that it needs explaining, how it could possibly have achieved any degree of respectability.[92]

No major historian of science today accepts it.

Professor David Bentley Hart states: "It is not difficult to demonstrate the absurdity of the claim that Christianity impeded the progress of science."[93] The conflict theory is grounded on ignorance of the history of science. John Hedley Brooke, Professor of the History of Science at Oxford, comments on the myth of the victory of science over religion: "The legend, once created, became part of the folklore of science."[94] He claims that even the supposed victory of Huxley over Bishop Wilberforce in the Oxford debate of 1860, was fabricated by Huxley 31 years after the event. He calls Huxley a brilliant self-publicist, who made it all up. Overwhelmingly science and religion have been in harmony. The conflict myth has been debunked.

Of course none of this is to deny, that some forms of religion have in the past constricted the human spirit, rather than enlightened and inspired it; and some today still do. So we need to distinguish those forms of religion and faith that are life-giving, from those that are life-denying. As Jesus said: "I am come that you should have life and life in all its fullness." (John 10:10) Some churches and religions have fallen short and warped this vision with a prescriptive and dogmatic approach, which cramps human freedom. Our greedy and selfish society thinks buying goods on credit, to impress people we don't care for, is the road to happiness. We need the message of the great spiritual leaders of the past, who pointed to a life founded on love and the service of others, as the keys to a fulfilled life. So a religious outlook can still provide a valuable yardstick and make it easier to resist the powerful pressures of living in our consumerist societies, driven by social media.

To sum up: it is baffling that the bizarre utterances of Christopher Hitchens should become a Number 1 best seller. Richard Dawkins maintains science and religion are in conflict, and so he has to misrepresent Einstein and claim Newton was a fake. Did he misunderstand Max Jammer's book, or set out to mislead? Dawkins also thinks evolution and God are incompatible; Charles Darwin thought the opposite. Do we believe the organ grinder or his monkey? Hawking proposes M-theory to explain the origins of the universe. Roger Penrose, Paul Davies and John Lennox and others dismiss this as groundless speculation, for which there is not a shred of evidence. Lennox claims it amounts to a triple self-contradiction.

The facts of science point to the existence of God: namely, we know that this universe exists, and secondly that it is fine-tuned for life. The greatest scientific minds, Newton, Darwin and Einstein, all believed that the evidence points to an intelligent mind behind the universe. The suggestion that there are other universes, is, as Paul Davies says, the last refuge of the atheist. It is mere metaphysical speculation: literally so, because it goes beyond the physical universe that we know. Large parts of physics have become a fact-free zone of mathematical speculation. In some ways it is like a cult, with pressure to conform and become a devotee.

It may come as a surprise to some folk, that the case for God is so strong, and the case for atheism so weak. It is a great shame that the media in general do not give both sides of the argument. Because the overwhelming majority of great scientists have concluded that the most elegant answer to the riddle of this finely tuned universe is God. Also one can't help wondering whether atheists are shrill, aggressive and abusive because their arguments are so weak?

Lastly a quote from Einstein:

We are in the position of a little child entering a huge library filled with books in many languages. The child knows someone must have written those books. It does not know how.... The child dimly suspects a mysterious order ... but doesn't know what it is. That, it seems to me, is the attitude of even the most intelligent human being toward God.[95]

References

[1] Charles Darwin, Letter to John Fordyce, 7 May 1879. Darwin Correspondence Project, 'Letter no. 12041', http://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/DCP-LETT-12041 (accessed on 11 May 2016)

[2] Einstein, in a conversation with Prinz Hubertus zu Löwenstein, in Löwenstein's book Towards the Further Shore (London: Victor Gollancz, 1968), p.156, quoted in Max Jammer, Einstein and Religion (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999), p.97

[3] Premier Radio, Unbelievable with Justin Brierley, 20 September 2010

[4] Ken Wilber, Quantum Questions (Boston: Shambhala, 2001), p.41

[5] Wilber, Quantum Questions, p.84

[6] Christopher Hitchens, God is Not Great (London: Atlantic Books, 2007), p.13

[7] Hitchens, God is Not Great p.5

[8] Hitchens, God is Not Great p.192

[9] Richard Dawkins, The God Delusion (London: Transworld Publishers, 2006), p.261

[10] Hitchens, God is Not Great p.18

[11] Hitchens, God is Not Great p.13

[12] Hitchens, God is Not Great p.56

[13] Hitchens, God is Not Great, p.57

[14] Hitchens, God is Not Great, p.60

[15] Hitchens, God is Not Great, p.47

[16] Hitchens, God is Not Great, p.16

[17] Hitchens, God is Not Great, p.10, (his emphasis)

[18] Hitchens, God is Not Great, p.115

[19] Hitchens, God is Not Great, p.117

[20] Hitchens, God is Not Great, p.118

[21] Hitchens, God is Not Great, p.192

[22] Hitchens, God is Not Great, p.213

[23] Hitchens, God is Not Great

[24] Albert Einstein, 'Science and Religion', in Albert Einstein, Ideas and Opinions (New York: Crown, 1954, 1982), p.46, quoted in Jammer, p.31

[25] Dawkins, The God Delusion, p.41

[26] Dawkins, God Delusion, p.34

[27] Dawkins, God Delusion, p.37

[28] G.S. Viereck, Glimpses of the Great (New York: Macauley, 1930), quoted in Jammer, p.48

[29] As Reference 2

[30] Albert Einstein, Letter to Phyllis Wright, 24 January 1936. Einstein Archive, reel 52-337, quoted in Jammer, p.93

[31] Z. Rosenkranz, Albert through the Looking-Glass (Jerusalem: Jewish National and University Library, 1998), pp.xi, 80, quoted in Jammer, p.151

[32] Einstein in conversation with William Hermanns, in William Hermann, Einstein and the Poet (Brookline Village, MA: Branden Press, 1983), p.132, quoted in Jammer, p.123

[33] E. Salaman, 'A Talk with Einstein', The Listener 54 (1955): 370-371, quoted in Jammer, p.123

[34] E. Strauss, 'Assistent bei Albert Einstein', in C. Seelig, Helle Zeit – Dunkle Zeit (Zurich: Europa Verlag, 1956), p.72, quoted in Jammer, p.124

[35] Einstein, Ideas and Opinions, p.255, quoted in Jammer, p.132

[36] H.G. Kessler, The Diary of a Cosmopolitan (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1971), p.322, quoted in Jammer, p.40

[37] Albert Einstein, The Quotable Einstein, ed. Alice Calaprice (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005), pp.195-6

[38] Lincoln Barnett, The Universe and Dr. Einstein (New York: Dover Publications, 1948-1985), p.109

[39] Albert Einstein, Letter to an unidentified addressee, 7th August 1941. Einstein archive reel 54-927, quoted in Jammer, p.97

[40] Einstein, 'Science and Religion', op.cit

[41] 'Has Science Buried God?' Dawkins vs Lennox Debate, at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, Oxford, on 21st October 2008. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J0UIbd0eLxw (accessed on 11 May 2016)

[42] Dawkins, The God Delusion, p.123

[43] Isaac Newton, Letter to Richard Bentley, 10 December 1692, www.newtonproject.sussex.ac.uk/view/texts/normalized/THEM00254 (accessed on 11 May 2016)

[44] Isaac Newton, cited in J.H. Tiner, Isaac Newton: Inventor, Scientist and Teacher (Michigan, Mott Media 1975)

[45] Cited in Rules for methodizing the Apocalypse, Rule 9, from a manuscript published in Frank E. Manuel, The Religion of Isaac Newton (London: Oxford University Press, 1974), p.120

[46] Debate at Wellington College between Richard Dawkins and Richard Harries, a former Bishop of Oxford, on 4th December 2009. Reported in Daily Telegraph 5th December 2009

[47] Charles Darwin, Autobiography, pp.92-94, available at http://darwin-online.org.uk/content/frameset?itemID=F1497&viewtype=text&pageseq=94 (accessed on 11 May 2016)

[48] 'Another ungodly squabble',The Economist, 5th September 2010

[49] Darwin, Letter to John Fordyce. Darwin Correspondence Project, 'Letter no. 12041', http://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/DCP-LETT-12041 (accessed on 11 May 2016)

[50] Stephen Jay Gould, 'Impeaching a Self-appointed Judge', Scientific American 267, No.1, 1992, pp.118-121

[51] Dawkins, God Delusion,p.81

[52] Dawkins, God Delusion, p.260

[53] John Marsh, The Liberal Delusion (Bury St. Edmunds, Arena Books, 2012)

[54] Stephen Hawking, The Grand Design (London: Transworld Publishers, 2010), p.180

[55] Hawking, Grand Design, pp.8-9

[56] Peter Atkins, Creation Revisited (London: Penguin, 1994), p.143

[57] The Independent, 22nd October 2011

[58] Premier Radio, Unbelievable with Justin Brierley, 20th September 2010

[59] Paul Davies, Templeton Lecture, 1995

[60] John Lennox, God and Stephen Hawking (London: Lion Hudson, 2011), p.32

[61] Financial Times, 4th September 2010

[62] Review of The Grand Design, in Scientific American, 13th September 2010

[63] Craig Callender, New Scientist, 2nd September 2010

[64] 'Understanding the Universe', The Economist, 9th September 2010

[65] Dwight Garner, 'Many Kinds of Universes and None Require God', New York Times, 9th September 2010

[66] Former Amazon Books Product Description page for the book

[67] Quoted on front cover of some editions of Peter Woit's book Not Even Wrong

[68] Lee Smolin, The Trouble with Physics (London: Penguin 2006), p.352

[69] Robert Laughlin, quoted in The Guardian, 8th October 2006

[70] Wikipedia page on Stephen Hawking

[71] Fred Hoyle, 'The Universe: Past and Present Reflections', in Engineering and Science, November 1981, pp.8-12. The quote is from page 12

[72] Antony Flew, There is a God (London: Harper One, 2007), p.96

[73] Paul Davies, 'What Happened before the Big Bang?', in God for the 21st Century, ed. Russell Stannard (Philadelphia: Templeton Foundation Press, 2000), p.12

[74] Paul Davies, Templeton Lecture, 1995

[75] Paul Davies, The Mind of God (Penguin, 1992), p.16

[76] Paul Davies' lecture given in Oxford at the Oxford Playhouse attended by the author

[77] Comments by Roger Penrose in A Brief History of Time, a documentary by Errol Morris based on Stephen Hawking's book of the same title. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Brief_History_of_Time_%28film%29

[78] Ken Wilber, Quantum Questions (Boston: Shambhala, 2001), pp.ix-xii (his emphasis)

[79] Wilber, Quantum Questions, p.41

[80] Wilber, Quantum Questions, p.161

[81] Wilber, Quantum Questions, p.84

[82] Wilber, Quantum Questions, p.91

[83] Wilber, Quantum Questions, p.175

[84] Wilber, Quantum Questions, p.208

[85] H.J. Blackham in Objections to Humanism (London: Penguin, 1965), p.109. In the book leading humanists criticise their own beliefs

[86] Bertrand Russell, A Free Man's Worship, cited by H.J. Blackham in Objections to Humanism, p.104

[87] Paul Davies, The Mind of God, p.16

[88] Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus-Logico Philosophicus, trans. D.F. Pears and B.F. McGuiness (London: Routledge and Keegan Paul, 2001), sections 6.52-6.522, pp.88-89

[89] Ludwig Wittgenstein, Diary entry 11th June 1916, cited by Hans Küng in What I Believe (London: Bloomsbury, 2009), p.72

[90] Einstein's essay 'Cosmic Religious Feeling', included in Ken Wilber Quantum Questions, p.104

[91] John Lennox, God's Undertaker (Oxford: Lion, 2007), p.27

[92] Colin Russell, Beliefs and Values in Science Education (Buckingham: Open University Press, 1995), p.125

[93] David Bentley Hart, Atheist Delusions (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), p.99

[94] John Hedley Brooke, Science and Religion (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), p.41

[95] Viereck, Glimpses of the Great, quoted in Jammer, p.48